Our agreement with the private landowners demands that the sites of these prospects be intentionally secreted until, and if, we are granted authority to reveal the localities. This private land is posted and regularly patrolled by the ranching community. Intruders will be introduced to the Sheriff.

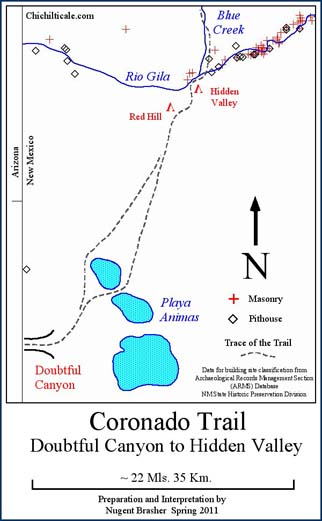

Our exploration team has discovered three Coronado campsites. The New Mexico Historical Review has published Reports on two of these – Kuykendall Ruins and Doubtful Canyon. Our discovery at the Slash SI Ranch in Catron County, New Mexico will be reported in a future issue of the Review. The University of New Mexico Press has published our interpretation of the Coronado Trail from the international border at Sonora and Arizona to Hawikku in New Mexico.

I have written that the Following and the Retreating armies traveled slower than the Advance party, necessitating more campsites for those two larger and more cumbersome groups. This means that the Following and Retreating armies might have used additional, less suitable campsites along the trail. Based upon this premise, the team is currently exploring two prospects along the trail between Doubtful Canyon and Hidden Valley.

We propose that the Advance Party, the Following Army, and the Retreating Army all camped at Rock-White-in-Water at Doubtful Canyon and at Hidden Valley on the Río Gila. The Advance Party, composed of horsemen and fleet-of-foot indios amigos, would have traversed this flat, sparsely-vegetated stretch in one day. The more burdened Following Army, traveling northbound, likely required two days. The southbound Retreating Army likewise probably required two days. This presumption results in an opportunity to explore for Coronado campsites between Doubtful Canyon and Hidden Valley.

Our team contends that Native Americans guided the Captain General over an old and established trade route. Consequently, the campsites should be located along that trade trail, thereby demonstrating the exploration potential of the trail itself.

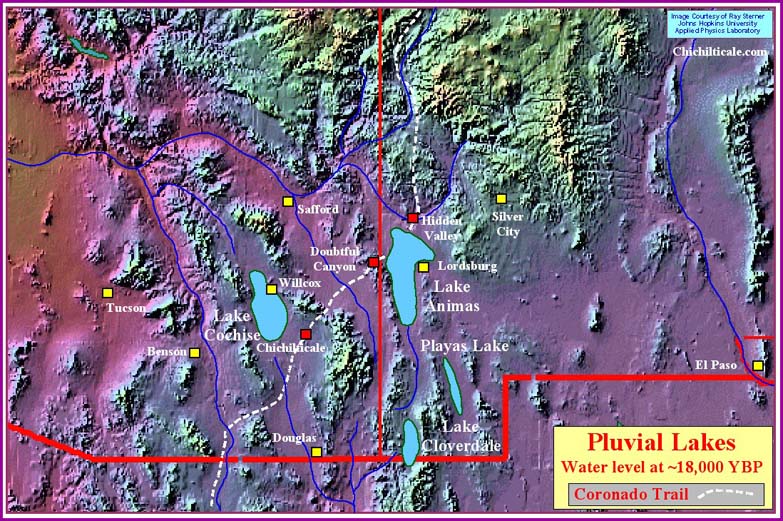

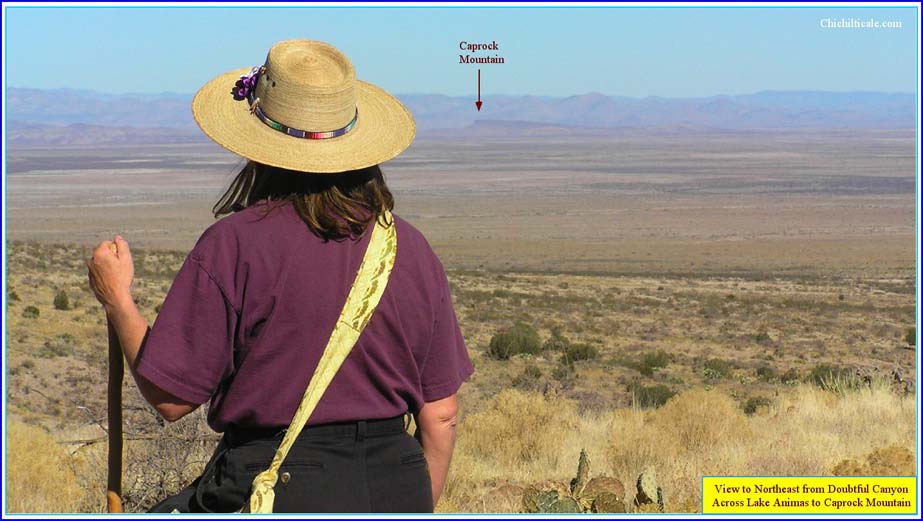

Our proposed trade trail between Doubtful Canyon and Hidden Valley is anchored on each end by those two locations. Between the two points spreads Lake Animas, a salt playa (lakebed, saltflat). This pluvial lake is one of four within the region: Lake Cochise, Lake Animas, Lake Cloverdale and Playas Lake. Two of these lakes, Cochise and Animas, are quite large, while Cloverdale is smaller, and Playas smaller still. All are “closed lows” topographically. Accepting that dating pluvial lakes is imprecise at best, such lakes in the Greater Southwest do, however, exhibit a history of containing water at times, and at other times being dry. Considering Paleo-Indian and Archaic time, the lakes of the Greater Southwest were full ~18,000 YBP (years before present), ~13,500 YBP, ~9,000 YBP, ~5,400 YBP, and ~3500-4000 YBP. Afterwards the lakes began to dry and never refilled. Lake Cochise and Lake Animas appear to adhere to this general temporal arrangement. Lake Playas appears to break from the pattern – it refilled ~1100-500 years ago.

Lake Cloverdale is truly a temporal anomaly when compared to the other three pluvial lakes. This lake at the extreme southern end of the Animas Valley appears to have been full 20,000-18,000 YBP, 5000-2000 YBP, 1000 YBP and 500-300 YBP. This record does not support other pluvial lake chronologies. For example, Lake Cloverdale appears not to have been full ~13,500 YBP and ~9,000 YBP, times when Lake Cochise and Lake Animas recorded high stands. Another discrepancy is that Lake Cloverdale appears to have been full ~1,000 YBP, when Lake Cochise and Lake Animas had receded.

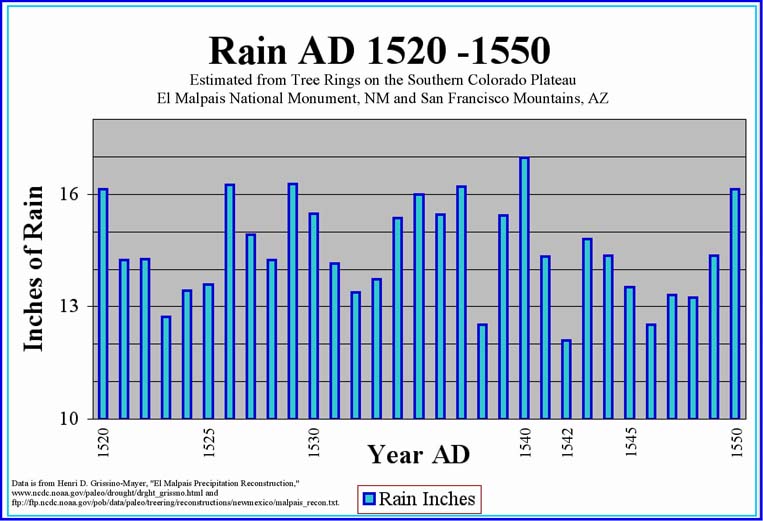

Of most interest to my inquiry into the Coronado Expedition is the claim that Lake Cloverdale was full ~500-300 YBP. During this time the Expedition passed by Lake Animas, located at the northern end of the Animas Valley. It is counter-intuitive that within the same valley, separated only by a low drainage divide, that one lake would be full and the other mostly dry, being that rainfall was the source of water for each lake. If Lake Cloverdale was full, then Lake Animas most likely contained a substantial amount of water. This would have impacted the route of the Expedition.

Irrespective of this anomaly, it is certain that ancestral pluvial Lake Animas was full at times, and dry or almost dry at others. As Lake Animas dried, the water level retreated to produce a contemporary lake north of modern Interstate 10 composed of three “pods” where water accumulates. I refer to these as the south, middle, and north pods, although the local name for the middle pod is Dry Lake. Depending upon rainfall, the contemporary lake can be totally dry, or it can contain varying amounts of water in specific places.

Experienced east or westbound travelers attempting to cross the lake, even when the pods appeared dry, followed a trail between the pods. Teamsters negotiating the Butterfield Stage route crossed the lake between the south and middle pods (Butterfield Rise). Inexperienced travelers suffered problems. John Russell Bartlett and his party found themselves mired in Lake Animas on 30 August 1851. Modern recreationalists often seek local ranchers to help extract their bogged-down vehicles where they have amateurishly ventured off roads to drive onto the lakebed, which to their eye seems dry, but is actually quicksand.

The various parties of the Coronado Expedition had to cross or circumvent Lake Animas. The Advance Party was at Lake Animas on 4 July of the modern calendar. This is the beginning of the summer monsoon. The year of 1540 was a wet one. It is likely that Lake Animas contained water in all three pods, and possibly enough water so that the pods merged into one larger lake. If Lake Animas followed the pattern of Lake Cloverdale, then it might have been almost full. If the lake pods had merged, or if the lake was truly full, then northbound Captain General Francisco Vázquez de Coronado and his Native American guides would have been forced to pass along the western shore of the lake to its northern end before bearing northeast toward Hidden Valley. Such a course would have taken them near Big Sandy. If the lake was not full, rather had water only within individual pods, the Advance Party could have been directed by its guides over a route between the middle and northern pods, through a passage I call Hackberry Rise.

The Following Army was at Lake Animas in early October of the modern calendar. Being a wet year, the pods likely held water, and were possibly even merged into one lake. If so, as had Coronado before them, the high-water travelers would have passed by Big Sandy, or the low-water travelers would have crossed through Hackberry Rise.

In 1542, a dry year, the Retreating Army reached Lake Animas in late April, the dry season of a dry year. Most likely the pods held water, and certainly held quicksand. The pods may have even been merged into a single larger lake. Depending upon the lake level, like the groups before them, the southbound army would have passed by Big Sandy or through Hackberry Rise.

During the years 1539 – 1542, at least eight small parties passed between Doubtful Canyon and Hidden Valley. These groups may have traveled at a pace decidedly distinct from those of the Advance Party, and the Following and Retreating armies. Such parties may have found Willow Spring or Big Sandy to be convenient campsites.

There is no mention in any of the Coronado chronicles of a body of water that could have been Lake Animas.

Regardless of the routes of the northbound Advance Party, Following Army and smaller parties, these travelers would have reached the eastern side of Lake Animas, where they would have encountered terrain seemingly lacking any geographically defined corridor of travel other than a straight-line projection toward Hidden Valley. The southbound Retreating Army and smaller parties would have departed Hidden Valley over the same terrain as the northbound travelers had arrived at the Rio Gila.

While a straight-line bearing might seem advantageous to an explorer, such is not always the case. The space between the eastern side of Lake Animas and Hidden Valley is vast and offers many possible pathways. The myriad of modern livestock trails attest to this. The possible travel corridor is so wide as to be detrimental to efficient and effective exploration, and experienced explorers will naturally seek a reason to select the most probable path.

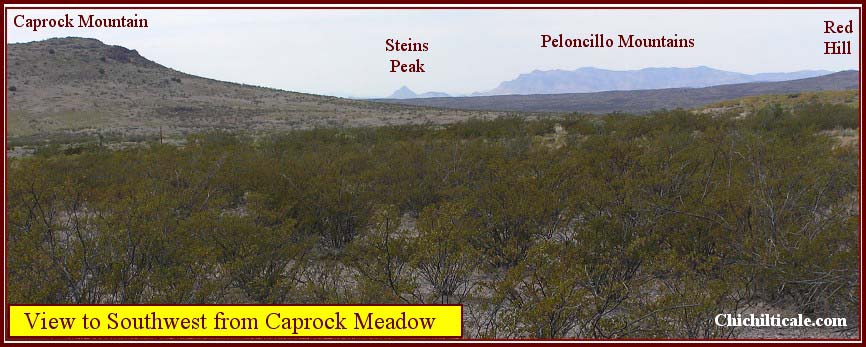

As the northbound travelers approached Hidden Valley, they reached the low mountains on the south side of the Rio Gila. The Black Mountains and the Caprock Mountains presented obstacles to be bypassed. The bypass for northbound travelers is marked by Red Hill, with the trail around the eastern side of that landform. It is likely that the guides for the Advance Party and the Following Army pointed the travelers at Red Hill upon departing the eastern shore of Lake Animas. While this presumption narrows the possible corridor, it does not provide a definitive trail. Southbound travelers departing Red Hill are forced to aim at Steins Peak in Doubtful Canyon. This circumstance results in a wide travel corridor detrimental to exploration. Landmarks alone cannot determine a definitive route.

Had Coronado and his guides encountered an actual pathway on the ground connecting Doubtful Canyon and Hidden Valley, they would not have been forced to rely solely on landmarks. Although I can today observe no such beaten path across Animas Valley, nevertheless, I believe that a trade trail existed, and I will present evidence of my presumption while, at the same time, defining the two prospects under consideration.

During 2002 into early 2004, prior to my confessed fascination with Coronado, I explored for trails that could have been used by Clovis hunters. This pursuit focused me on pluvial lakes in southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico. I studied and mapped Lake Cochise in the Sulphur Springs Valley, Lake Cloverdale in the southern Animas Valley and Lake Animas in the northern Animas Valley. I conducted non-intrusive surface reconnaissance in order to observe exposed artifacts. My mapping and reconnaissance was directed at finding locations prospective as Clovis campsites. During that time I composed a document titled “The Bootheel: A Critique of Southwestern Archaeological Exploration.” This manuscript recorded, analyzed and critiqued the archaeological exploration history of the region from the appearance of Adolph Bandelier in southwestern New Mexico in December 1883 to archaeologists of the present time.

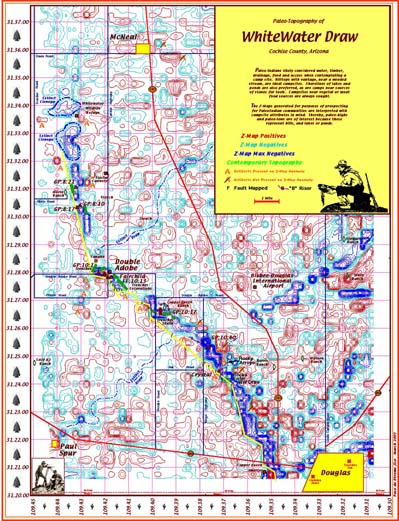

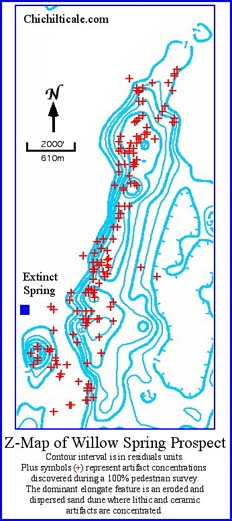

Among the various techniques I employed for surface exploration was a map type conceived in the 1980s by my research partner and me that we anointed as a Z-Map. Although the map was developed as a petroleum exploration tool, I recognized it as useful in the exploration for archaeological sites.

Four data elements are required to construct a Z-Map: latitude, longitude, elevation, and ID number of elevation station. During development of the process for archaeological purposes, data was gathered by hand, which was labor-intensive and error-prone. Handwork included utilizing hardcopy topographic maps as a data source. North-south and east-west lines were drawn at 15-second intervals across each quadrangle map. A grid node was created where lines crossed. Each grid node was assigned a unique ID number. Latitude, longitude and elevation were recorded at each ID number. Subsequently, the data gathering process was improved to reduce errors, speed the process and enhance resolution of the Z-grid. This was accomplished by employing software to access commercial Digital Elevation Models (DEM) to generate a dataset that provides an accurate 5-second data grid.

Mapping software is then utilized to access the dataset and to generate a map grid. This grid is called the topographic-grid. The topographic-grid is contoured at an appropriate interval to create a topographic map. Depending upon the gridding algorithm and the mapping parameters selected, the resulting topographic map might or might not resemble the original topographic map from which the data was derived.

Continuing to employ the mapping software, the topographic-grid is treated by applying a specific algorithm that smoothes the topographic-grid. This produces a smoothed-topographic-grid. The smoothed-topographic-grid is then subtracted from the original structure-grid. This results in the Z-grid. The Z-grid is contoured at an appropriate contour interval. The result is a Z-Map. It is tempting to consider the Z-Map as a common “best fit” residuals map. However, the Z-Map is distinct and appears so to an experienced interpreter.

By selecting the contour interval that best reveals the topography, contouring the Z-grid results in a Z-Map that can be interpreted as a paleo-topographic map. Interpretation of the Z-Map results in recognition of features such as eroded hilltops, tilted terraces, extinct watercourses, washed-out beaches and buried bogs. Application of the interpretation generates a map depicting campsites, village sites, ponds, streams, canals and probable prehistoric routes and trails. The Z-Map technique is especially appropriate for low-relief terrain. Prairies, plains, lakebeds and deserts are good places to employ the Z-Map. Valleys between rugged mountains are suitable.

I have generated Z-Maps in several areas to test the application to archaeological prospecting. Field checking of anomalies has verified the usefulness of this technique. Included in the field checks were examinations of non-prospective and random terrain. The clear result is that artifacts were most often associated with Z-Map anomalies and that artifacts are most often absent where anomalies were absent. Many sites were discovered that were previously unknown, even to a knowledgeable landowner. Scores of camps have been found by locating eroded hilltops overlooking extinct water sources and by locating terraces along buried watercourses. Sites, caves and petroglyphs have been found by following trails revealed by the Z-Map. A Clovis site was discovered by following a curvilinear feature interpreted as a washed-out beach. Many sites were found on seemingly featureless terrain where the Z-Map indicated isolated eroded knolls.

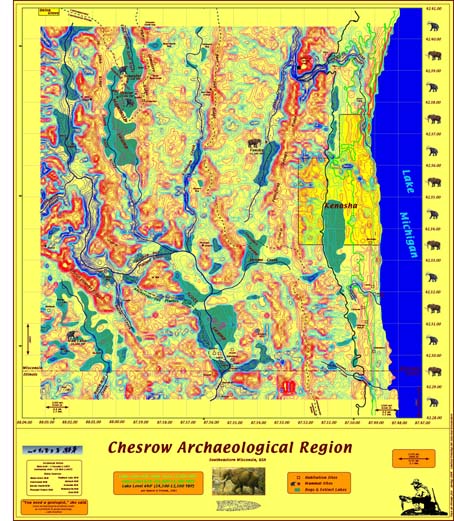

During the period 2000-2001, the Z-Map technique was applied to an archaeological reconnaissance project at Rancho San Alfonso in Sonora, Mexico. Interpretation of the Z-Map led to the investigation of dozens of anomalies considered to be prospective aboriginal habitation sites. A high percentage of these anomalies proved to be sites, a significant majority of them being previously unrecorded by field archaeologists who had surveyed the area. In 2002, the Z-Map technique was applied in the Sulphur Springs Valley of Arizona. Again a high percentage of anomalies proved to be archaeological sites. Furthermore, the Z-Map proved helpful in defining the geology relevant to geoarchaeological investigation. The Z-Map technique was applied in Wisconsin in 2004 in association with the Chesrow Complex as a means to prospect for Pleistocene megafauna sites and aboriginal habitation sites that had potential for radiocarbon dating.

I have insisted that Coronado followed an old, well-established, long distance trade trail that also connected villages. While acknowledging that the southwestern New Mexico – southeastern Arizona region had become uninhabited, except for nomads, long before Coronado arrived, I am, nevertheless, convinced that pre-abandonment settlements existed, and that these serve exploration because archaeological sites of substantial size are reliable indicators of trade trail locations.

Previously I presented a map generated in 2009 showing pithouse and masonry sites as recorded in the Archaeological Records Management Section (ARMS) database. This map lacks sites along the proposed Coronado Trail south of Red Hill and north of Doubtful Canyon. Neither Willow Spring or Big Sandy is recorded as a pithouse or masonry site in the ARMS database, thus neither is shown on that map.

In 2003, more than a year before the Flints introduced me to Coronado, I applied the Z-Map technique at Lake Animas, New Mexico. My purpose at the time was to explore for sites of aboriginal habitation or presence on shoreline depositional features. The resulting Z-Map provided an enhanced version of the lacustrine setting. My eye was immediately drawn to a pronounced linear feature that I now call Willow Spring.

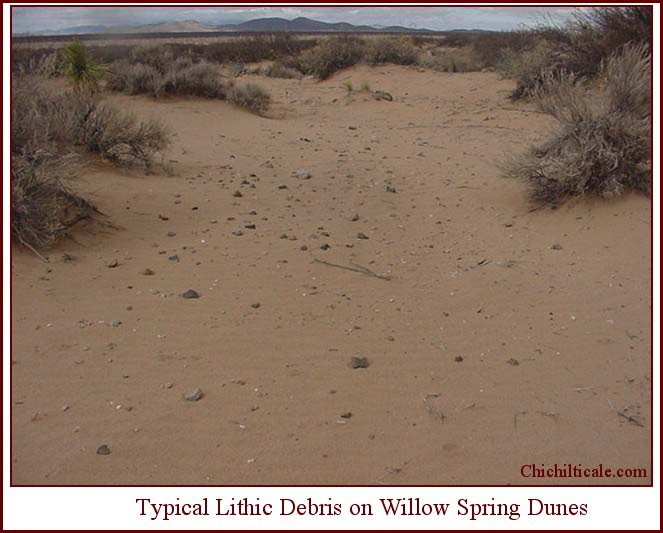

Subsequent field exploration resulted in the discovery of a trend of camps three miles long and one-half mile wide containing thousands of lithic and ceramic artifacts. The geomorphic feature is an elongate field of low-relief sand dunes. Desert willows grow on the crests of the dunes. Blowouts occur sporadically throughout the dune field. Tracks of rabbits, coyotes, snakes, birds, javalina, cougar and deer reveal the abundant diverse wildlife that thrives within the dunes.

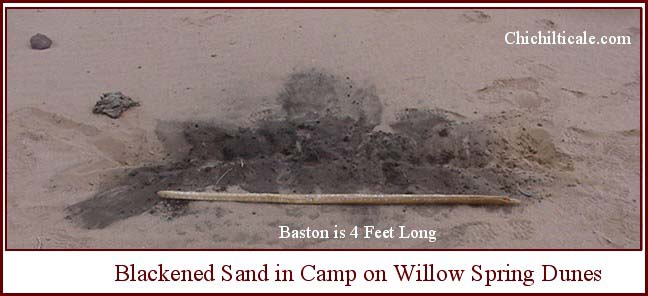

Native Americans also thrived in the dunes. We recorded scores of camps. We seldom walked very far without finding fragments of rocks broken by humans. Camps were both small and large. Smaller camps could be contained within a circle of 25-foot radius. Some individual camps were greater than 200’ x 100’ in size. Some groups of camps joined together to create a zone of artifacts more than a thousand feet long and 200’ wide. Some blowouts within zones of commingled camps contained lithic debris sufficient to totally cover the ground. One camp measured over 250’ in length and about 80’ in width, and contained a considerable amount of ceramic. Associated with the ceramics were lithic debris of chips, broken groundstones and fractured rocks. One pile of burned rocks discovered there was remarkable for the amount of carbon still remaining on both the rocks and in the sand. This degree of occupation rivals certain sites in coastal Sonora and surpasses anything I have seen on the Gray Ranch in southern Hidalgo County, New Mexico. Only two sites at Double Adobe, Arizona are so widespread as some of the concentrations of lithic artifacts on the dunes of Willow Spring.

The Willow Spring dunes contain artifacts dating from Paleo-Indian through Archaic and Prehistoric and to the Spanish Contact and even more recent. Paleo-Indian material culture is represented by one limace, identified by the late Dr. Robson Bonnichsen, founder and former director of the Center for the Study of the First Americans, currently associated with Texas A&M University. This tool is associated with the Eastern USA Clovis tradition, and first described at the Vail Site in Maine. Limaces are rare and virtually unknown in the Western United States. Richard Michael Gramly describes the limace as “A narrow, slug-shaped, unifacial, flaked stone tool having steep edge angles and a high dorsal surface that is often rounded. Limaces have been termed awls, and narrow side scrapers, and unifacially flaked drills, and boats and Hendrix scrapers, and a host of other names. Limaces have been analyzed exhaustively, and these analysts have coined the term flakeshaver. They surmise that these tools were hafted in socketed handles and used as a chisel on hard substances.”

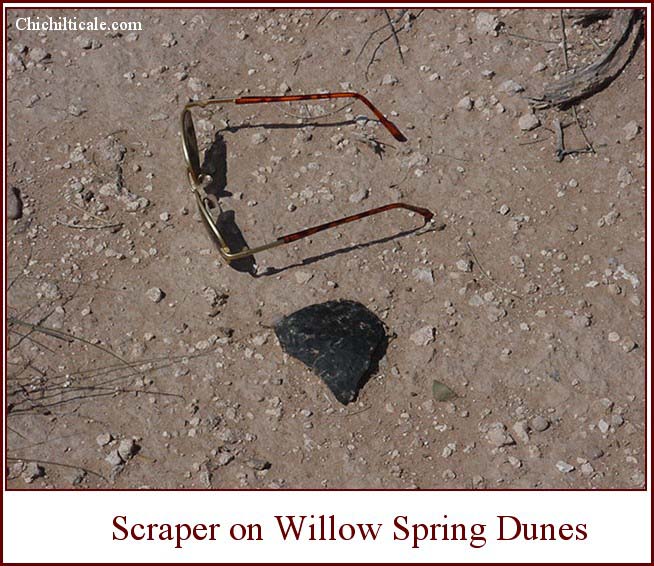

Archaic period artifacts number in the thousands. The bulk of the artifacts consist of lithic debris – mostly chips and fragments. The most common rock employed is black basalt. Piles of burned and broken rocks, some still containing blackened sand, are numerous. Projectile points are almost all “Pinto-Gypsum,” which appear as San Pedro style found at Chiricahua sites. One of the points found on the Willow Spring dunes is of Abasolo typology, which dates 8000-6000 YBP. Scrapers are abundant. Two drills fashioned from black basalt were observed.

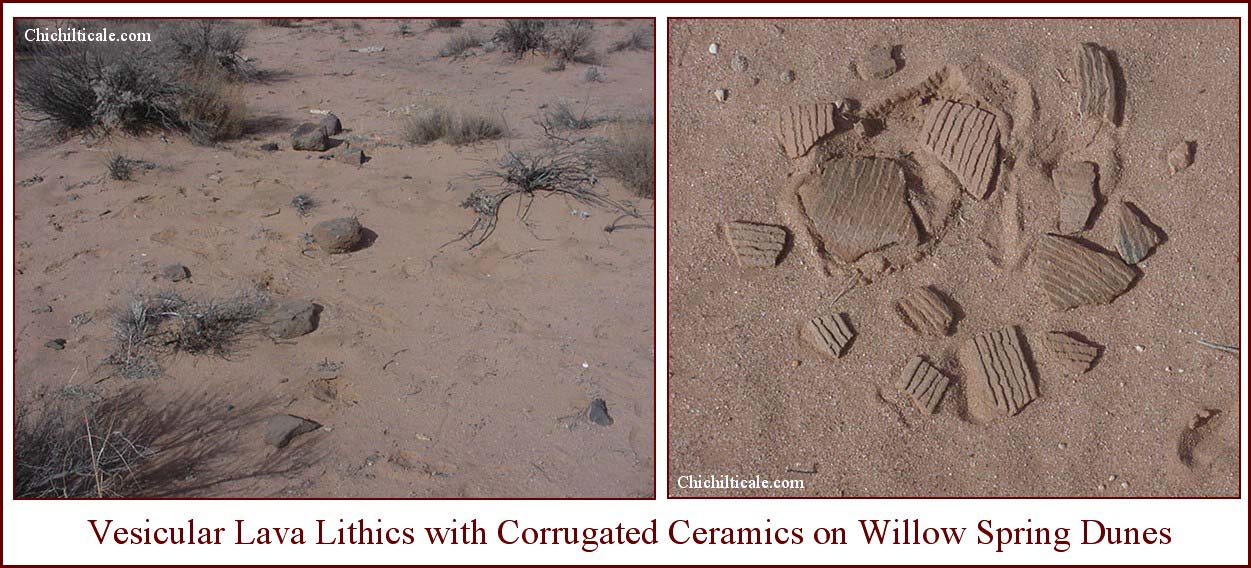

Material culture of the Prehistoric period includes ceramic. Sherds are of Tonto Polychrome, Gila Polychrome, Ramos Polychrome, Chupadero Black-on-white, El Paso Polychrome, Ramos Black, Playas Red, Playas Red Incised, Hohokam Red-on-buff, Mogollon Corrugated, Mimbres Black-on-white, Tularosa Black-on-white, White Mountain Redware, Pinedale Polychrome, Mogollon Red-on-brown, Madera Black-on-red, Carretas Polychrome, Tucson Polychrome and Maverick Mountain Polychrome. Observed lithics include a single full-grooved axe and several small black obsidian projectile points associated with corrugated ceramics.

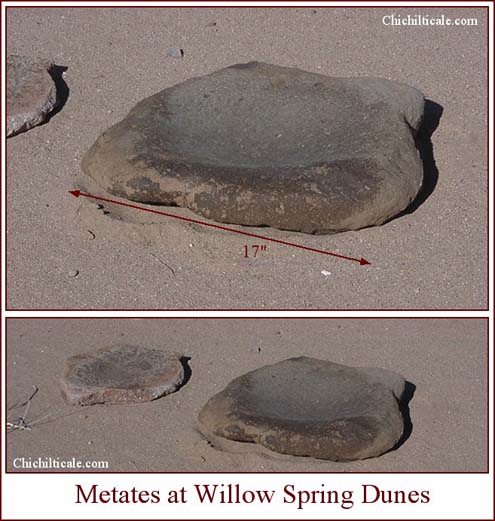

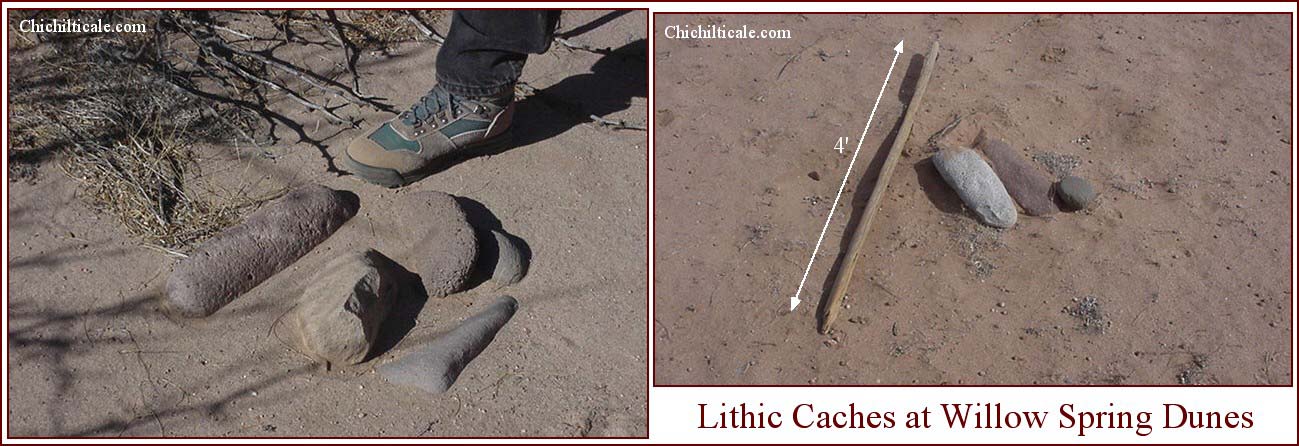

Groundstones number in the hundreds. Included are metates, manos, and pestles, the latter often in caches. These stones are often intact, but most are broken. One expansive portion of the Willow Spring dunes contained metates notable for their consistency of rock type. Almost without exception these metates were formed from blocky, heavy, smooth, dense, black igneous rock. Some metates were two square feet or more in size and weighed upwards of 20 pounds. These big slabs had been transported from miles away, which is apparent because the nearest possible sources are the Summit Hills, the Black Mountains, or the Peloncillo Mountains. The camps where ceramics are found contain more groundstones than the non-ceramic camps.

Despite the sedimentary setting that limits Willow Spring prospect to a sand, silt, gravel and cobble environment, there are many exotic rock types present on the dunes. These include rhyolite, ignimbrite, diorite, gabbro, chert, chalcedony, obsidian, jasper, serpentine, and olivine. A vesicular lava is notable for its association with corrugated sherds. Many of the exotics are large rocks. Cores of exotic rock the size of small footballs display obvious scars where blades and flakes have been knocked off. As I pointed out, some rectangular metates are more than two feet in length. All these rocks were deliberately carried from distant sites to Willow Spring.

The abundance, origin, and ages of the lithic and ceramic artifact assemblage indicate that the Willow Spring dunes were frequented and periodically occupied for thousands of years. The diversity of the exotic rocks and of the cultures represented by the ceramics indicates that visitors to the site came from all directions. Willow Spring was at a crossroad. It lies along the east-west route that geomorphically best accommodates travelers moving in those directions, as evidenced by its proximity to the historic routes of the road to the California gold fields, the Butterfield Trail, the Southern Pacific Railroad, and the Interstate highway. Also it lies along one of the most favorable north-south routes – north to Hidden Valley and the Rio Gila “only” crossing at Blue Creek, and south to Casas Grandes and the Rio Yaqui Trail. Willow Spring lies within the corridor of Emil Haury’s map depicting the “Probable Route of the Diffusion of Maize in the Greater Southwest,” and it lies on Stephen Lekson’s Chaco Meridian.

The totality of these spatial and temporal traits suggests that Willow Spring almost certainly lies on an extinct trade trail. The elongate symmetry of the site fits the topographic model I have proposed for Coronado campsites. The most prospective portion of the site is on private land centered on an extinct spring. These attributes serve to elevate Willow Spring to a top-tier prospect.

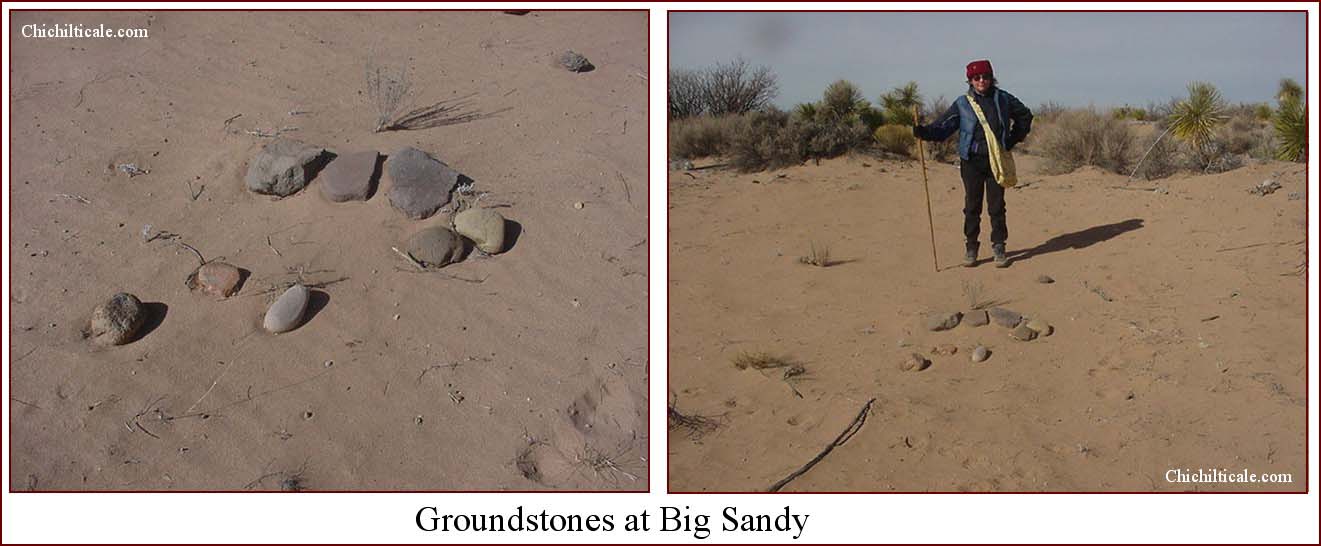

Had Lake Animas held enough water to prevent passage through Hackberry Rise, Coronado’s travelers would have passed around the northwestern end of the lake. Big Sandy is located on private land in this area. Like Willow Spring, there is an extinct spring present, as well as sand dunes. Unlike Willow Spring, however, Big Sandy lacks an elongate water course.

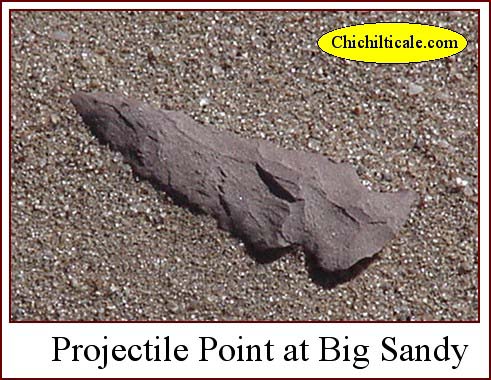

The archaeological setting at Big Sandy contains a similar Paleo-Indian, Archaic and Prehistoric assemblage to Willow Spring. Paleo-Indian material culture is represented by one Clovis and one Folsom projectile point. The Archaic is represented by “Pinto-Gypsum” points, burned and broken black basalt, and groundstones. The Prehistoric setting is dominated by ceramics, which appear in greater numbers than at Willow Spring. Exotic lithics are scattered throughout the site.

Big Sandy and Willow Spring are four and a half miles apart and each is positioned within the trade trail corridor. The appearance of Coronado’s expeditionaries at either site would have depended upon the water level of Lake Animas. This circumstance serves to funnel the travelers to a specific site, thereby creating high quality prospects.

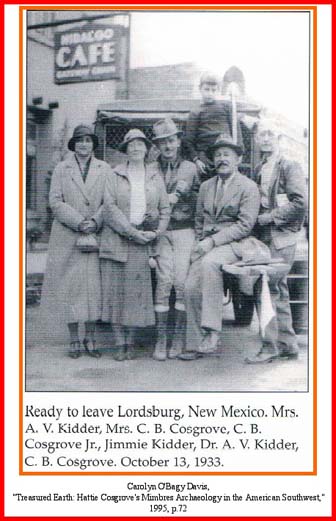

My unpublished manuscript, “The Bootheel: A Critique of Southwestern Archaeological Exploration,” contains a section on Harriet “Hattie” Silliman Cosgrove and Cornelius Burton Cosgrove. These avocational archaeologists contributed mightily to Southwestern archaeology, and much of their work occurred in southwestern New Mexico. In 1933 they conducted an excavation at Pendleton Ruins near Lake Cloverdale on the Gray Ranch. On the night of 12 October, the excavators spent their “last night in a bed and took their last real baths for almost two months at the Hidalgo Hotel.”

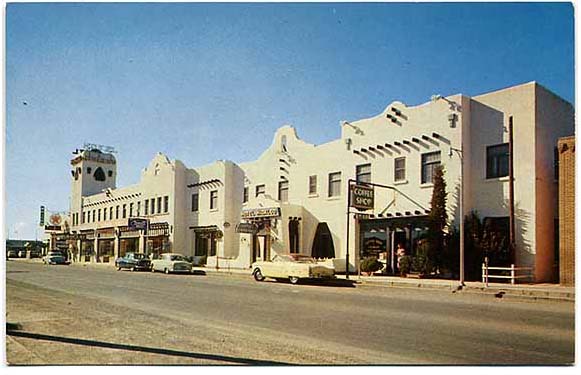

Before Interstate 10 replaced Highway 80 through Lordsburg, the Hidalgo Hotel was a famous sojourn for Southwestern travelers, including me as a child motoring with my parents. The Interstate killed the old hotel and it remains closed and vacant, despite the fact that the Hidalgo served as a “gatehouse” for many explorers heading into the desert. On 4 November 2005, Mr. Earl Wagner guided Karen Brasher and me through the hotel. In recognition of this historic lodge, I am including the photographs taken that day, as well as sharing the notes Karen scripted as we listened to Mr. Wagner.

The Hidalgo Hotel pre-dates 1883. The building on the west side of the hotel bears an inscription reading W H Small 1883, and the bricks of that building cover the west windows of the hotel. Entrance to the hotel was through a tile-adorned sidewalk into a narrow and modest lobby, perhaps not really a lobby, rather a corridor to the reception behind a Dutch-door. Beside the door was a writing board and key-hang board.

After checking in, guests climbed a stairway to the second floor rooms. The upstairs hall walls were skip trowel brown.

Communal bathrooms were the rule. Radiators provided heat to the hallways.

Individual rooms sported green skip trowel walls, lavatories and chamber pots. All rooms had radiators and transoms over the door. Floors were linoleum with floral design. Room #30 was the highest room in the building. Rooms #14 and #23 were suites. Chambermaids and guests emptied their chamber pots in the scat bucket on the back roof. Inside rooms had windows that opened into the hallway. A breezeway with scoops to force air into rooms provided circulation. End rooms were cooler.

The Hidalgo Hotel complex occupied the entire block. A postcard from the 1950s illustrates the complex at that time.